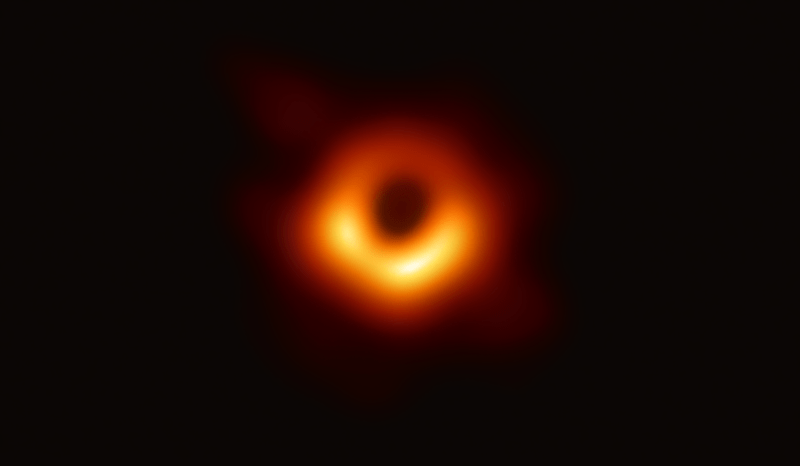

Credits: Event Horizon Telescope collaboration et al.

My dear daughter,

Let’s talk about black holes.

When I first took your mother out to have pizza I talked a great deal about black holes.

Yes, your father is a bit peculiar. More on that in the future.

So, talking about black holes is really exciting. Perhaps they will teach you in school black holes are these massive dead stars and their gravity is so strong not even light can escape.

Well, it’s not inaccurate, but there is more. According to current scientific and mathematical knowledge, they are a region of space so curved that light can’t escape this curvature. In fact, it’s a region of space with infinite curvature, which seems to be absurd.

We know since Einstein published his General Theory of Relativity that gravity is a geometric description of space. It curves itself in the presence of matter or energy. We are grounded to Earth because we are immersed in the curved space-time near Earth. Yes, Einstein (and others) also proposed (and were proved correct) that there are no geometrical differences between the 3 spatial dimensions we experience every day and the time dimension. Hence, space-time.

Where do black holes come from? The stars you see in the night sky are these huge spheroids of incandescent gases. Mostly hydrogen. They are so big, their sheer weight crushes hydrogen atoms in their core, producing helium and energy. Two hydrogen atoms have more energy than one helium atom, so this nuclear reaction produces lots of energy. We experience that energy here on Earth as heat and light, for example. That nuclear reaction is called fusion.

If a star is big enough, when it exhausts its hydrogen fuel, it will start burning and fusing the helium, which releases even more energy. Then it will start burning heavier elements. When that happens it goes supernova – it’s this huge star explosion. This happens over the course of millions and millions of years. After the explosion, if the resulting matter is heavy enough, it will collapse on itself, surpassing a density threshold and forming a black hole.

As far as we know, there are lots of black holes out there in the Universe. They are very important to galactic formation. There are stellar black holes and their heavier relatives – massive black holes, which happen when lots of black holes start joining together. There might be a massive black hole in the center of every galaxy. The one in the center of our galaxy, the Milky Way, is called Sagittarius A*. It keeps the galaxy together, with our solar system in it.

For some time we thought black holes were kinda boring, I mean, there wouldn’t be much difference between them. They were supposed to have mass, angular momentum and electric charge. So all black holes would look alike, and because of that scientists would say “a black hole has no hair.”

There were some problems with that early model of black holes and the 2nd Law of Thermodynamics: the total entropy of a system can never decrease over time.

The problem was, if black holes are so tight, matter and energy inside them can’t reorganize; particles would have nowhere to move to, their configuration would never change. So black holes would have no entropy and that would be a violation of the 2nd law.

This other really smart guy called Stephen Hawking conjectured black holes have entropy and it would be proportional to the area of their event horizon divided by the Planck area. The black hole would have different internal states and information would leak back to the universe as Hawking radiation coming from the event horizon: as components of virtual particles separating from their counterparts falling below the event horizon. We call them virtual particles, but they actually exist and carry energy. They come and go into existence in any volume of space. So, in quantum physics, there is no such thing as a truly empty space.

Black holes would eventually evaporate by emitting Hawking radiation, but it could take a very long time, maybe longer than the estimated number of years the universe would still have before imploding on a big crunch or coming apart if it doesn’t stop expanding. But we’re talking billions of years here.

That’s all for today.

Love,

Dad